In the history of building doors at Hull Millwork, we have made nearly every mistake possible. The wrong wood, the wrong technique, bad execution; whatever the mistake, we have made it. We have also made good decisions in projects that still failed. The truth is, it isn’t easy to build wood doors—residential or commercial—that last 100 years.

Use, exposure, and abuse all contribute to determine a door’s life. The good news is that after years of success and failure, we have learned that by focusing on three key attributes, you can build a historically accurate door that functions well for decades.

Wood doors are terrifically challenging, whether they are new or historic: rotting wood, cracked panels, fading paint, and loose joints are all plagues on their integrity. Modern hardware does not help door life, either. Door closers can wrench and wrack doors, while panic hardware can weaken key areas of a door’s joinery. These challenges are the reason many large manufacturers have turned to plastic and composite-wood materials, which is not a perfect solution.

Another major challenge is modern HVAC systems, which exert a tremendous amount of stress on doors. Here in Texas, we have intensely hot summers. Sometimes by midday, a door with a southern exposure can bake to over 130 degrees on the exterior. Yet, on the inside of the building, the same door is greeted by an acclimated temperature set at 72 degrees: a near 60-degree swing within 2 inches of wood. This puts amazing stress on the wood, the panels, and the finish.

Keep in mind that 100 years ago, doors had the advantage of virgin and oldgrowth wood, no false climatization from HVAC, and hearty lead-based paint coatings that wore like a Kevlar jacket in the elements. In the last 50 years, we have hindered the functional longevity of wood doors; thus, we need to design and build smart so our doors can succeed.

Three Keys to Long-Lasting Doors

The three keys to building long-lasting historic doors—wood choice, construction methods, and finish—are all important. We believe that wood choice is the most important. Wood quality today is not what it was 100 years ago. Since we no longer have virgin timbers and oldgrowth lumber readily available, we must use woods that can withstand the elements.

Illustrations by Robert Leanna

Illustrations by Robert Leanna

TIP: A good rule of thumb is to use native or regional woods. Using woods that are native to your climate perform better than woods from other parts of the country. Do not use western pine in Florida. Do not use eastern white pine in Houston. Native woods tend to behave and last longer when they are kept in their native climate. The western pines, for all their faults, do perform better in the dry West than they do here in North Texas.

Wood Choice

Forest Product Labs, an independent testing lab focused on wood performance and longevity, did a study on the decay resistance of the heartwood of major woods. (Note: The heartwood of a tree is the longest-lasting, most mature part of the tree, closer to the center and often darker in color that sapwood. Sapwood is young wood residing on the outer layers of the tree and is not as stable or rot-resistant as the heartwood.)

Forest Product Labs tested common woods like oak, walnut, pine, and fir to determine which ones lasted the longest. They sorted their findings into three categories: resistant or very resistant; moderately resistant; and slightly resistant or nonresistant. In other words, distinguishing good wood and crap wood.

Choosing woods that are resistant or very resistant is the key. These woods include white oak, redwood, oldgrowth cypress, walnut, and cherry. The second-tier, moderately resistant woods are Douglas fir, new cypress, eastern white pine, and longleaf yellow pine. These second-tier woods can still perform well in the right conditions, and we occasionally use them.

The last category, nonresistant woods, should be avoided. These include western pines, red oak, poplar, birch, beech, and maple. Western pines are sold by common names like sugar pine, radiata pine, and ponderosa pine. Unfortunately, these are inexpensive woods and get quite a bit of use from large manufacturers. While improvements in technique and wood preservatives advance each year, I think using a wood known to fail on exterior applications is very risky.

Unfortunately, choosing the right wood isn’t enough; you also need to specify the right cut. This means specifying the proper orientation of the grain to the face of the door, so that the door is more stable. There are three cuts of wood: plain sawn (moves the most), rift sawn, and quarter sawn (moves the least). Note in the diagram how the plain-sawn boards have a lot of grain movement on the face of the board. A plain-sawn piece of wood 8 inches wide could move 1/8 inch in width or more, depending on moisture in the environment. By contrast, the same board, rift-cut or quarter-sawn, is much more stable.

Our company uses Tidewater red cypress, longleaf yellow pine, and quarter-sawn white oak for most of our historic projects. These woods have great historic precedent, and we commonly find them on historic buildings. These woods have a proven track record of success. When using longleaf pine, it is often salvaged material, which can be expensive and harder to source, but it is also virgin timber and therefore will last for generations.

For those times that historic wood type isn’t an issue, we typically use sapele and Spanish cedar for exterior work. These are excellent, stable woods that we trust and have a track record of long term-performance. Bottom line: Choosing the right wood and the right cut of wood can help increase a door’s life by 10 times.

TIP: Another trick we have stolen from the past is the use of a drip edge on a door. This type of detail was common in France and on better doors in America in the early 1900s. A drip edge sits on the outside bottom of exterior doors. Any door that is exposed to the rain needs a drip edge, because modern thresholds are not enough. A drip edge kicks the water away from the bottom of the door and keeps it from leaking.

Joinery

The second key to a long-lasting door is the joinery. Proper construction techniques can make a big difference, especially for exterior doors. According to historic precedent, the best and longest-lasting joints were mortised and tenoned together and then pegged (see illustration). We’ve found that this type of joinery lasts longer and is stronger than any doweled door or short mortise door. For a door that is going to experience a lot of stress, a mortise-and-tenon door with a deep tenon (at least 3 inches) is hard to beat.

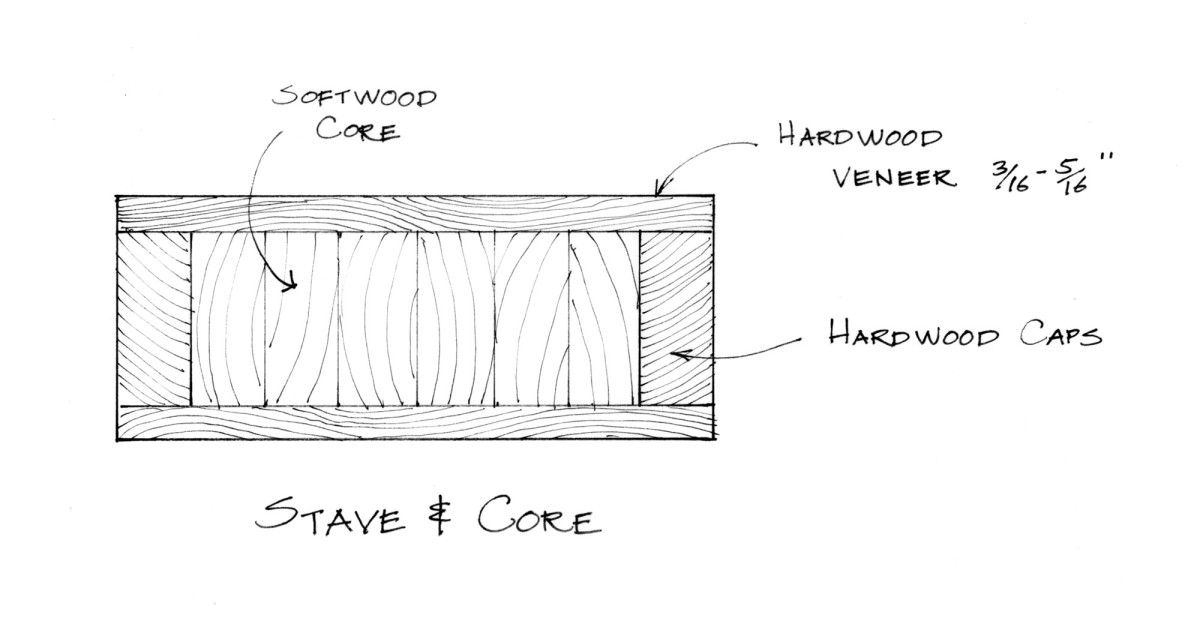

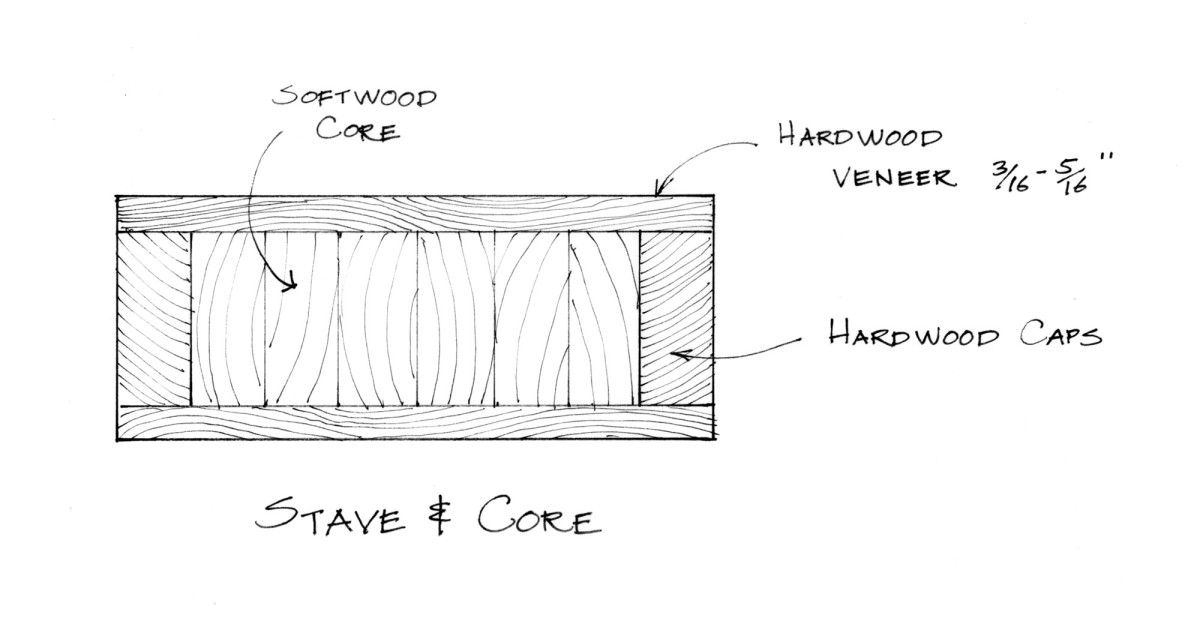

Around the turn of the 20th century, another type of historic door developed that we find on the best historic buildings: stave core doors. We find them to be more stable than single-piece wood doors.

A stave core door is a wood door, whose inside core is constructed of many small pieces of wood that are reoriented to create inner stability (see illustration). This inner core of smaller wood slices creates great structural stability by changing the direction of wood movement inside the door. This keeps the door from twisting and bowing. Because it is structurally stable there is less stress on the door’s joinery, which in turn helps the door last longer.

The key to a good stave core door is a thick outer veneer. The best doors of the early 1900s had veneers that were ¼-inch thick. Compare this to modern door veneers which can be as thin as 1/16-inch to 1/32-inch. A thicker veneer protects the core longer and in turn the door is more durable.

Finally, we believe mortise-and-tenon joinery is key. There are many ways to join a door stile to the rails. Developed in the late-1890s, dowels—short round wood pieces—were a cheaper and faster way to glue up a door. Our experience in over 25 years of restoring doors is that the longest-lasting doors have mortise-and-tenon joinery.

Remember that glues were substandard before the 1930s. Animal-hide glues were most common. These glues are not water resistant and can come loose and break down when exposed to moisture. Because these glues did not hold up, early craftsmen, and then manufacturers, often put a peg through the mortise-and-tenon joinery, which created a mechanical joint that lasts much longer. Today, with many high-tech glues, you can be lulled into thinking joinery doesn’t matter, but from our experience glue is a factor but only about 10 percent of the solution. If you want your doors to last for over a generation, good joinery matters.

We once helped a client who had tall French doors with nearly no overhang that constantly leaked. They were old doors and she wanted to save them. Instead of building an overhang or using an invasive trick, we simply added drip edges to the bottom of her doors. It stopped the water leakage, and the homeowners were very pleased.

The Finish

The final secret to long-lasting doors is the finish. Water and sun are the enemies. Water causes wood to expand and contract. Joints can quickly become compromised, and—if you have an inferior wood—rot can soon set in. The sun’s UV rays destroy the fiber and quality of the wood. Water and sun can be controlled with a good finish. In many ways, it is the last defense a door has. If you can keep the door under cover and away from the sun, your doors will last much longer.

My quick rule of thumb for the best door finishes is, don’t stain them. There is not good-quality, readily available clear wood sealer on the market. A clear wood sealer allows the sun’s UV rays to break down the pigment of the stain or finish and is not a long-term solution. I remind my clients who want or require a stain finish that the door will need a new coat of finish every one to two years. You may get a little longer life in other climates, but here in North Texas it is a poor choice.

Paint is the best finish for exterior doors. I usually add two conditions. First, don’t paint an exterior door a dark color. The dark color rule is especially true here in Texas. In our hot climate, painting a door a dark color can increase the surface temperature of the door by 20 degrees. As I stated earlier, this change in temperature puts a tremendous amount of stress on a door.

Second, and equally important, make sure any paint you use is high-gloss. This is a lesson from experience. We don’t use cheap paints, but even with semi-gloss finishes, I sometimes return to a job a couple of years later and see that the paint has started to turn chalky and is breaking down. When the paint surface begins to break down, it allows moisture in, and then your troubles literally can bake in. Our experience is that high-gloss paints—the best being Fine Paints of Europe in Vermont—create a hard finish or coat that is easy to clean and lasts longer.

While complying with these rules is likely not always possible, especially for historic projects, we hope our guidelines give you your best chance for success.

This article originally appeared on Traditional Building.